High profile activist campaigns on climate change and plastics are a sign of the times, indicating the increasing ability of NGOs to ‘make the political weather’.

Recent dramatic blockades of bridges and road junctions by Extinction Rebellion climate activists in central London are a salient reminder that there is still fire in the belly of Britain’s environmental movement. Robert Blood, Managing Director of NGO tracking and issues analysis firm SIGWATCH, explains what this means for corporate chiefs.

While disrupting traffic, stopping trains and supergluing body parts onto buildings gets the attention of the media and politicians, much less noticed is the rise in public and private pressure by activist groups on big business generally within the last twenty years. The financial sector has been a particularly lucrative target for activists, who see investors as a lever for forcing recalcitrant boardrooms to change their behaviour. On climate, instead of trying to get energy and transport firms to negotiate away their livelihoods, activists target the banks, investment funds and pension schemes which fund them, demanding they divest from coal, oil sands and fracked gas and other “extreme fossil fuels”. Modelled on the US campus South African Apartheid divestment campaigns of the mid-1980s, this “Follow the Money” strategy has worked spectacularly well. Within the last two years most of Europe’s major banks and insurers have announced or strengthened anti-coal and oil sands policies, as have several major banks in the US, despite (or because of) the blatant hostility to the issue shown by their government.

Nor is the rise in influence of activist groups limited to climate change. The ‘mainstreaming’ of environmental and social governance (ESG) considerations by institutional investors in the last ten years is due in great part to NGOs pressing financial institutions to show they can be responsive to the needs of society after the 2008 banking crash.

With activists demanding corporate action on a wide range of pet concerns as diverse as plastics and indigenous rights, sustainability and supply chain standards, and circular economies and animal welfare, how should boardrooms prioritise their response?

Chart 1: Plastic pollution issue - increasing NGO campaigning anticipates rising public concern

One way that companies can detect activist-driven issues coming down the track is to monitor the collective behaviour of campaigning groups. When new issues start to gather momentum, one of the first things that happens is that existing campaigns intensify, and more activist groups join in with their own campaigns. Once this increased campaigning diffuses through mainstream and social media, the public begins to react, which stimulates even more campaigning and thus an even stronger public response, until the issue reaches an infamous ‘tipping point’ of overwhelming outcry.

This is how an issue like plastics apparently came out of nowhere in 2018 to put leading FMCG brands and retailers on the spot over their deep dependency on plastic packaging and other throwaway items. Plastics as a source of environmental concern dates back at least fifty years, but campaigning only began seriously to rise in 2016 with the microbeads problem. So why did it suddenly spill over? As Chart 1 shows, activists had been piling on the pressure for many months before. In the UK, David Attenborough’s ‘Blue Planet’ BBC TV programme showing turtles swimming in plastic waste was also an accelerating factor, but this chart, which plots global collective NGO activity on plastics (orange line) and public concern (blue line), defined by the relative number of Google searches per month on the same issue, shows NGO campaigning on plastics pollution and single-use plastics was increasing strongly at least a year earlier.

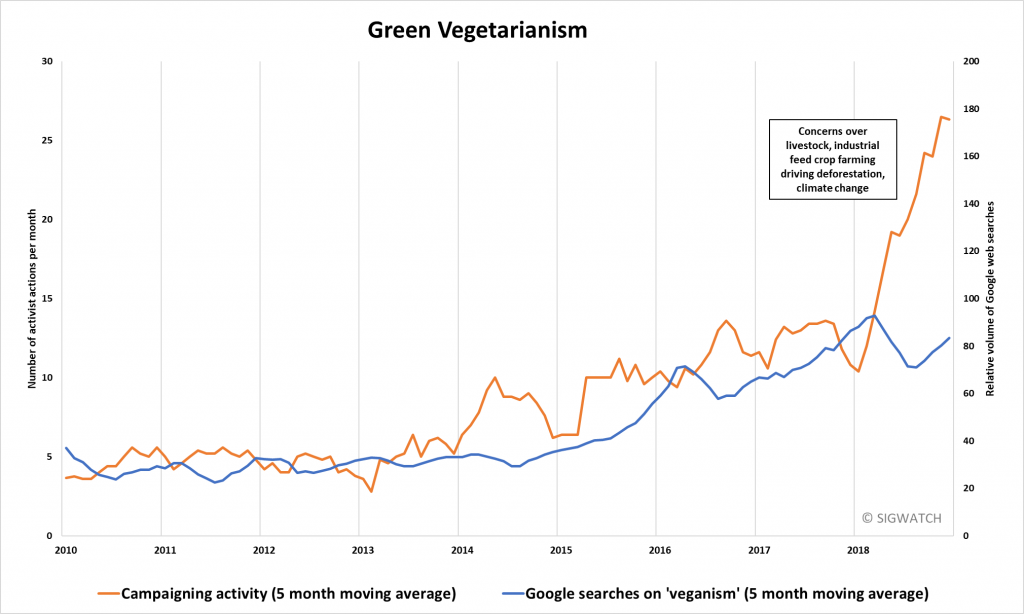

We have seen similar predictive correlations with other issues such as fracking (shale gas) in the US Using the same approach, we predict that the next ‘plastics’ will be ‘green vegetarianism’: an increase in vegetarianism and veganism driven not by traditional concerns like health and animal rights but by environmentalism. We are likely still in the early stages of the issue cycle, but already in the data (see Chart 2), we can see a big rise in campaigning as a host of environmental groups press the case for less meat eating and reductions in livestock agriculture, and this is well in advance of the rise in public interest. If it persists, the consequences of this shift in eating habits will be felt globally, from agribusiness combines involved in meat and feed grain production down to businesses offering on-site catering.

Chart 2: Rise of Green Vegetarianism

We know NGOs ‘make the weather’ on environmental and social issues. The predictive power of their campaigning shows that their impact is no accident, but rather, it is a result of activists’ ability to generate overwhelming public interest, which drives the political agenda and in turn, demands a corporate response or capitulation. Armed with foreknowledge of the next activist wave, companies have the chance now to ride the surf, rather than be dragged down by the undertow like some of their peers over the last twenty years.